Preliminary remark

In describing the individual mills, I refer exclusively to the book on the mills of Kourtaliotis and Kotsifou by Christos I. Makris (*), reproducing the essential content in my own words.

Land register entries of the Preveli monastery (made until about 1866) clearly show that the first mill (counted from the north) belonged to the monastery. Hence the name monastery mill or mill of Tzambeti, which is still in use. However, it is not clear whether the other four mills actually belonged to Preveli Monastery, although the land register entries speak of mills in the plural.

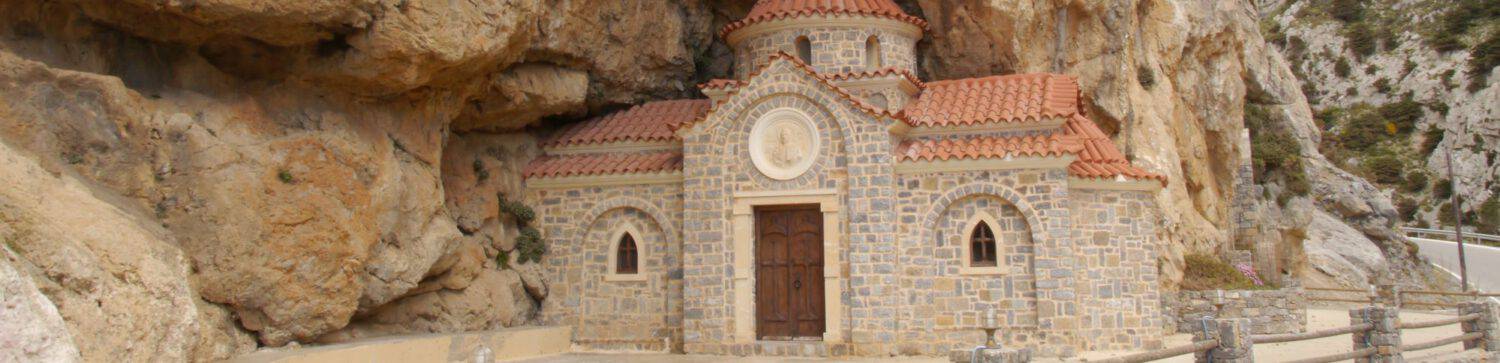

This mill comprised three mill sections, as can still be seen in the picture above. The middle inlet is pretty much 20 m high, making it the highest of the Kotsifou mills, about the same height as the Pigado mill in Souda. Its foundation has a width of 3 m and 2 m at the well inlet. There are no residential buildings for the miller and his family, as is otherwise the case with other mills. The sections of the mills, except for the fountains, seem to clearly belong to the style of Turkish rule, which of course did not suddenly appear as a virgin birth in the era, but had already emerged as a folk technique before that. This stone construction clearly continues in the villages until the Second World War.

Origin

The mills of Kotsifou are not mentioned in any Venetian documents. Unfortunately, for the curious, there is only the preserved oral tradition, but no inscriptions relating to the construction of the mills, just as there are none for the Preveli monastery. It seems that the mill was not built by the monastery, but by residents of Mirthios. Most of the mills on the Kotsifou were their work and hence their close, direct and geographical relationship with them. Many were sought-after employees of the millers. The monastery mill therefore seems to have been built in the Venetian era.

Their construction in the Venetian period is further confirmed by the fact that the two mills at Kourtaliotis, as well as the Pigado mill (Souda), date securely from this period. And even more precise, the monastery mill must, according to Makris’ personal knowledge, have been built by a group of Mirthiani when the Turkish threat was already in sight. The still Venetian conquerors reduced the pressure on the threat in order to win them over or not to provoke their enmity. There were many owners, and Mirthios very close. They also did not particularly appreciate the miller’s residence. With the imposition of the new conquerors, with the “change of scenery” (“αλλαξοβασιλίκια”), as the Cretans call it, they felt the threatening breath of the Turkish fort (Koulés) breathing down their necks and the claims of the Turks to the property of the village. So they decided to give their work to Preveli Monastery to save it from possible appropriation by the new feudatories. This also made it possible to continue operating the mills.

According to the tradition as set out by Charalambos Chatzidakis, the construction must have taken place around 1700 and the dedication to the monastery of Preveli around 1750, when the services of the monastery were already established.

Recent history

In 1939 this mill was bought by Manelis Theodorakis from the village of Kanevos in an auction for 92,000 drx. At the auction, bidders from the village of Mirthios (to whose local area the mill belongs) also took part, but they could not outbid Manelis. Since they had close ties to the mills of Kotsifou since it existed, and since there were millers among them, they did not like the idea of a foreigner taking over the mill. So, as a last resort, they tried to tear down and destroy the mill. In this dangerous situation for the new owner, he handed over 8,000 drx. to them, which calmed things down again.

Since Manelis had a lot of work and was also not particularly skilled in handling the farm and its maintenance, after three years he was joined by a business partner, Konstantinos Zambetakis (Tzambetis) from the village of Agios Ioannis. After several years, Zambetakis bought the mill in its entirety as sole owner, and so the mill received his name. During the years with two owners, they used it for a week at a time. In the weeks of the first owner, Stelios Tzellos (Tzellakis), a miller from Mirthios, took over the works and shared in the profits.

A few years after the German occupation, electric mills began to spread in the villages. Gradually, the water mills were abandoned. One of the flour mills, located 80 m below and of which only the well remains today, ceased to operate at the end of the German occupation. Presumably in 1962/63, the entire mill was finally abandoned.

News

Work on the mill complex has been underway since around 2019. The entire area was restored and visually upgraded. The 20 m high water intake was completely cleared of ivy, and the buildings at this intake were renewed and extended. The lower water intake with the fountain building was also restored.

As far as I know, residential units are to be built here. And possibly a mill museum?

(*)

Χρίστος Ι. Μακρής, Οι Νερομύλοι στα φαράγγια του Κουρταλιώτη και του Κοτσυφού

Ο Πηγαδόμυλος του Δήμου Φοίνικα Ρεθύμνης στην Κρήτη, σελ. 55

Translated: Christos I. Makris, The Water Mills in the Gorges of Kourtaliotis and Kotsifou

The Pigado Mill of the Municipality of Foinikas Rethimno Crete, p. 55